Posted by: Bobbi Miller, Conservation/Advanced Inquiry Program Zoology student at Miami University of Ohio and Project Dragonfly

As I prepared for my trip to Namibia, all the images from childhood television shows like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom and Daktari flooded my mind. Would I see a cross-eyed lion? Would Marlin Perkins stand back while Jim went over to examine the deadly puff adder? It didn’t really matter; I was going to Africa—the place of my childhood (and adult!) dreams.

But this was no photo safari complete with luxury accommodations. This was an Earth Expedition to Namibia, part of Miami University of Ohio’s Project Dragonfly Master’s Degree program. I was going there to learn.

There was the requisite coursework like cheetah biology, community based conservation and education, and conservancy management, but what I really learned was something much more important: the wildlife we so closely associate with Africa is in serious decline.

Our base of operations was the Cheetah Conservation Fund just outside of Otjiwarongo.

We’d be staying in cinderblock dorms while we learned more about the loss of African species to human/wildlife conflict, human settlement, and poaching. Naturally, the first animal on our list was the cheetah. Today there are only 10,000 cheetahs left in the wild, having disappeared from more than 70% of their natural and historic range. Where the cheetah remains, it often finds itself in conflict, as it takes the blame for livestock losses and can be persecuted and killed by ranchers.

Dr. Laurie Marker’s Cheetah Conservation Fund specializes in working with local ranchers to use livestock guarding dogs to protect their herds, safely corralling herds at night as a preventative measure. When livestock losses do happen, CCF works with ranchers to investigate. Taking the time to observe the prints left behind on the scene or the remains of the attacked livestock can help determine who the real culprit is—and many times it’s not a cheetah. Through this process ranchers are learning to live with the cheetah, rather than fear and kill it.

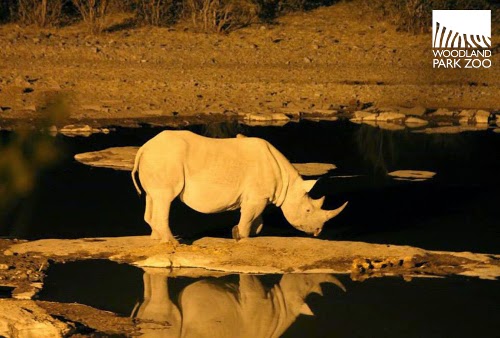

A trip through Etosha National Park meant seeing the sort of wildlife I had been dreaming of. We were delighted as our bus slowed to give us a glimpse of our first rhino. Upon closer observation we noticed open wounds and extreme emaciation. Life would likely be short for this rhino, adding to their endangered status even more. To date, the black rhino has suffered a population drop of approximately 98% due to poaching for rhino horns. A talk with a former Etosha wildlife ranger confirmed my fears— even in the park animals are not safe these days; poachers will track them and take them wherever they can find them.

And then it finally happened—we saw an African elephant. And not just one elephant, but a small family group with a very sassy youngster in the lead. It was magical. Standing just to the side of our bus was a small herd of the largest land animal.

And then it hit me—100,000 elephants had lost their lives in the past three years to poachers. This small family, so proud and strong, may not be here in the next 10-15 years. And not just this family group, the way things are going, unless poaching is stopped, African elephants could become extinct in the wild in my lifetime. And that is when the tears began to flow, and I thought about the conservationist Cynthia Moss and her statement, “We are going to lose the largest animal on earth just so people can have trinkets.”

But there is hope. Zoos are working hard to educate visitors about the realities of life in the wild. Like they say, it’s a jungle out there and life in the wild is not always pretty. Seeing an animal up close really does create a bond and builds a connection making you want to take action. Knowing and loving the animals we care for in the zoo made seeing them in the wild even more powerful, and reinforced how critically important it is to make sure we are taking steps to save them.

And for elephants (and rhinos), it’s critical that we act now. Through the 96 Elephants campaign, we’re shining a light on the illegal poaching of elephants for ivory. If you haven’t already, please lend your support to the campaign by adding your name.

Finally, human/wildlife conflict doesn't just happen in faraway countries. The issues that livestock ranchers in Africa have with big cats are very much the same issues ranchers in Washington state have with wolves. Taking lessons learned in other countries, where they’re making peaceful coexistence work, and applying it to what we do here in the states is a critical next step in protecting our environment and the species that live in it.

Africa was not only the place of my dreams, it is now permanently in my heart. If I walked away with anything, it is the profound meaning of this Namibian proverb:

Nothing could be truer.

As I prepared for my trip to Namibia, all the images from childhood television shows like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom and Daktari flooded my mind. Would I see a cross-eyed lion? Would Marlin Perkins stand back while Jim went over to examine the deadly puff adder? It didn’t really matter; I was going to Africa—the place of my childhood (and adult!) dreams.

But this was no photo safari complete with luxury accommodations. This was an Earth Expedition to Namibia, part of Miami University of Ohio’s Project Dragonfly Master’s Degree program. I was going there to learn.

|

| On the way to the Cheetah Conservation Fund. Photo by Bobbi Miller/WPZ. |

There was the requisite coursework like cheetah biology, community based conservation and education, and conservancy management, but what I really learned was something much more important: the wildlife we so closely associate with Africa is in serious decline.

Our base of operations was the Cheetah Conservation Fund just outside of Otjiwarongo.

|

| Welcome to the Cheetah Conservation Fund Centre. Photo by Bobbi Miller/WPZ. |

We’d be staying in cinderblock dorms while we learned more about the loss of African species to human/wildlife conflict, human settlement, and poaching. Naturally, the first animal on our list was the cheetah. Today there are only 10,000 cheetahs left in the wild, having disappeared from more than 70% of their natural and historic range. Where the cheetah remains, it often finds itself in conflict, as it takes the blame for livestock losses and can be persecuted and killed by ranchers.

Dr. Laurie Marker’s Cheetah Conservation Fund specializes in working with local ranchers to use livestock guarding dogs to protect their herds, safely corralling herds at night as a preventative measure. When livestock losses do happen, CCF works with ranchers to investigate. Taking the time to observe the prints left behind on the scene or the remains of the attacked livestock can help determine who the real culprit is—and many times it’s not a cheetah. Through this process ranchers are learning to live with the cheetah, rather than fear and kill it.

|

| Cheetah. Photo by Bobbi Miller/WPZ. |

A trip through Etosha National Park meant seeing the sort of wildlife I had been dreaming of. We were delighted as our bus slowed to give us a glimpse of our first rhino. Upon closer observation we noticed open wounds and extreme emaciation. Life would likely be short for this rhino, adding to their endangered status even more. To date, the black rhino has suffered a population drop of approximately 98% due to poaching for rhino horns. A talk with a former Etosha wildlife ranger confirmed my fears— even in the park animals are not safe these days; poachers will track them and take them wherever they can find them.

|

| A healthy rhino at a watering hole. Photo by Bobbi Miller/WPZ. |

And then it finally happened—we saw an African elephant. And not just one elephant, but a small family group with a very sassy youngster in the lead. It was magical. Standing just to the side of our bus was a small herd of the largest land animal.

|

| African elephant family. Photo by Monica Ackerley. |

And then it hit me—100,000 elephants had lost their lives in the past three years to poachers. This small family, so proud and strong, may not be here in the next 10-15 years. And not just this family group, the way things are going, unless poaching is stopped, African elephants could become extinct in the wild in my lifetime. And that is when the tears began to flow, and I thought about the conservationist Cynthia Moss and her statement, “We are going to lose the largest animal on earth just so people can have trinkets.”

|

| The little elephant was filled with personality. Photo by Kendra Hodgson. |

But there is hope. Zoos are working hard to educate visitors about the realities of life in the wild. Like they say, it’s a jungle out there and life in the wild is not always pretty. Seeing an animal up close really does create a bond and builds a connection making you want to take action. Knowing and loving the animals we care for in the zoo made seeing them in the wild even more powerful, and reinforced how critically important it is to make sure we are taking steps to save them.

And for elephants (and rhinos), it’s critical that we act now. Through the 96 Elephants campaign, we’re shining a light on the illegal poaching of elephants for ivory. If you haven’t already, please lend your support to the campaign by adding your name.

Finally, human/wildlife conflict doesn't just happen in faraway countries. The issues that livestock ranchers in Africa have with big cats are very much the same issues ranchers in Washington state have with wolves. Taking lessons learned in other countries, where they’re making peaceful coexistence work, and applying it to what we do here in the states is a critical next step in protecting our environment and the species that live in it.

|

| Life at the waterhole. Photo by Monica Ackerley. |

Africa was not only the place of my dreams, it is now permanently in my heart. If I walked away with anything, it is the profound meaning of this Namibian proverb:

“The earth is not ours; it is a treasure we hold in trust for future generations.”

Nothing could be truer.

Comments

Post a Comment